Penguin populations

There is a reason Tawaki remain one of the least known penguin species in the world, even though they are the only crested penguin to live reasonably close to humans. That reason is their preference to breed in thick and impenetrable rainforest.

Tawaki are not only difficult to see—they are also difficult to count. Yet knowledge about how many there are is key to understanding how their population is doing in the face of many environmental challenges, climate change being probably the biggest.

In the 1990s, a multi-year project, largely financed by and conducted with the help of tourists, searched most of the known distributional range of Tawaki and concluded that there were only between 3,000 to 7,000 birds, making Tawaki one of the rarest penguin species on earth.

However, when we started the Tawaki Project, we were invited by Southern Discoveries to come and visit Milford Sound. According to official records, there were only nine (9!) breeding pairs in the fjord, which to us sounded like looking for the proverbial needle in the haystack. But when we arrived, we found about 10 pairs at Harrison Cove within our first hour ashore!

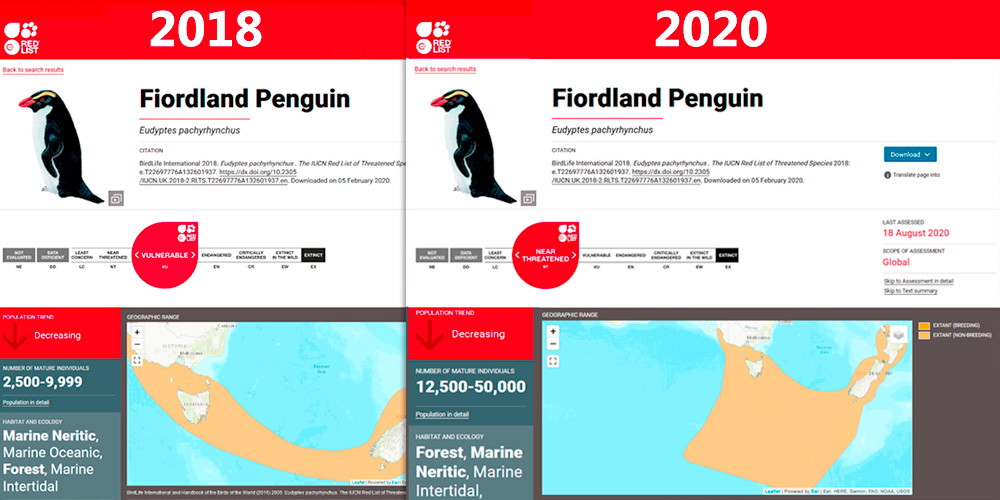

After two years working in Milford Sound, we concluded that there were around 160 breeding pairs in that fjord alone. This pattern was also apparent at all other sites we visited and looked for the penguins so that in 2020, the threat status of the species was revised by the IUCN Red List from “vulnerable” to the less severe “near threatened.” Tawaki was only one of 25 animal and plant species that year with an improved threat ranking!

The Tawaki Project has since continued to search for Tawaki nest sites throughout Fiordland. To date, we have mapped around 800 nest sites and colonies in Fiordland, representing at least 3,000 penguins—and we have only visited three of the 14 fjords. Not to mention that mapping each fjord completely will take multiple years. And, of course, there’s the entirety of the West Coast and Rakiura/Stewart Island to be done (although parts have been expertly counted by Robin Long already).

With penguins so difficult to count, how can we be sure that what we count one year is comparable with what we count in the following years? It is simple… we can’t. But we still need to understand if the population is doing well or not. To this end, we have established (and keep establishing) Automated Wildlife Monitoring Systems (AWMS) that identify penguins we have marked with PIT tags (aka “microchips” that are used in pets) over the course of their life. That way, we get a better understanding of the births, mortality, and recruitment which are key factors to determine whether a population is growing or declining.

From everything we have recorded to date, we assume that Tawaki are doing a lot better than previously thought. There are a lot more penguins than the 1990s surveys suggest, and the AWMS shows high survival rates indicating a healthy population. But as climate change progresses, and as new threats arise (e.g., introduced predators, seabed mining, changes in fisheries practices), it is vital to keep a finger on the pulse of the Tawaki population.

But what about the other crested penguin species in Aoteaora/New Zealand? One of them, the Erect-crested penguin or Tawaki nana hi is one of only four penguin species world-wide ranked “endangered” by the IUCN redlist. But despite being in a dire threat category, nothing has happened to investigate whether this ranking is appropriate and, if so, what can be done to change it.

To alleviate this shortcoming, we have recently started to gather first baseline data that will eventually provide clarity on the Erect-crested penguins’ population status. Unfortunately, first results are not nearly as rosy as it was for Fiordland’s tawaki.

But more work needs to be done. And we’re only at the very beginning of a momentous (and expensive) task.

To find out more about the monitoring we are doing, head over to the Tawaki Project website.